Doragon Returns - 10.8.2010

"If no one watched another Osore Pictures production again, that would be just as well. We would still continue to make movies."

The first Doragon movie was not a box office success. There’s an honest debate to be had if it was even given a wide enough release in Japan to turn a profit. According to what the Hino brothers said in interviews, there was a dedicated attempt by Toho - the company behind the Godzilla films - to suffocate and stifle any and all potential competition in the kaiju genre before they could gain any traction. Toho, they said, threatened to withhold their own movies from any theaters that showed kaiju films from competing studios. As one of the most popular film studios in the country, this resulted in only small theaters in the north of Japan and niche, specialty theaters that featured independent movies being the only places where Doragon played.

Though Toho did unquestionably dominate the nascent and emerging kaiju genre throughout the 60’s, by 1965, Daiei Film was seeing success with their own kaiju films such as Gamera and Daimajin. Given the wide release of these films, as well as others, the comments made by the Hino brothers on the matter are of dubious veracity.

Whatever the case may have been, the Hino brothers still claimed that the movie, despite its limited release, managed to make back its budget and some change.

In a 1979 interview held by the sci-fi magazine Starlog, Kazuo Hino was quoted as saying, The money is not important. We never made our films with the intention of getting rich. Film making has always been an exercise of artistic passion for us. It’s something we do as an expression of ourselves and the things that we love. If audiences love them as well, that is good, and I’m glad they enjoy our films. If nobody watches them, then that is also fine. We make our movies strictly for our own enjoyment. If no one watched another Osore Pictures production again, that would be just as well. We would still continue to make movies.

This, of course, raises the question that, if the Hino brothers were not financing their cinematic projects through profits generated by their movies, where were they drawing the funds from?

I suppose this is as good a time as any to speak more on the men behind Osore Pictures. The oldest of the brothers, Shuji, was born in the village of Morita within the Aomori Prefecture in 1922. Kazuo, the younger, would be born there in 1931. In between them, there was another brother, Osamu, born in 1928, and, later, a sister, Kaori, born in 1933, who would play the lead role in the brother’s film, Shigama-onna.

The family had two older siblings as well - Kouji and Azumi - both of whom died during the course of WWII, with Kouji being lost with the sinking of the aircraft carrier Ryujo, and Azumi, who had moved to Tokyo with her husband, perishing in a fire bombing raid. During the war, Shuji served aboard the battleship Nagato, and Osamu, despite being drafted, never saw action, as the war ended before he was deployed. Public records mention one last child - Shiho - born in 1935, though no other information could be found. Rumors say that Shiho died during birth, or during infancy, though these are unsubstantiated and likely to be false.

Outside of cinema, Shuji worked off and on as a copyright lawyer, occasionally stepping away from his practice to focus his efforts solely on film making. Kazuo worked a wide variety of construction-adjacent jobs, including trim carpentry and woodworking, house framing, and painting, all of which were talents that he would use in crafting props and sets for the Osore Pictures films.

The patriarch of the Hino family, Shuzo, was a well-to-do lawyer and the eldest son of a shipping mogul by the name of Jutoku. Though Jutoku Hino sold his shipping operation before Shuzo was of age, he did so for a handsome profit, as was the fortune of which his son inherited after his untimely passing after falling from a horse. This money, in turn, was inherited by his own children, the fortune of which was largely responsible for bankrolling the endeavors of Osore Pictures.

The brother claimed that their grandfather, Jutoku Hino, was a member of the kozaku, which was a system of peerage established after the Meiji Restoration in 1869. Jutoku Hino’s father, they said, held the title of Danshaku, which in the kozaku hierarchy would have put him on par with a European baron. Reportedly, he was given the land around the village of Morita as a gift for his loyalty to the Meiji emperor during the various military campaigns of the time.

This claim, so far as my research shows, cannot be corroborated. Perhaps the information necessary to justify it exists in Japanese sources I have no access to, but if it does, I couldn’t find it. Ultimately, there’s very little of what the brothers say that can be verified by external sources in Japanese, and effectively nothing on them was ever published in English. Their claims have nothing to be substantiated by aside from their own word. Whether they’re to be believed is really up to the individual to decide.

Following Doragon’s release, Osore Pictures would release another horror movie titled The Beautiful Woman in 1965, which once again starred their sister, Kaori. The titular beautiful woman is a youkai known as the kuchisake-onna - or the slit-mouth woman, in English - who takes an interest in a young man and, throughout the film, methodically kills everyone he’s close with in an attempt to drive him closer to her. Like Shigama-onna, there’s a psychological angle to the story in which it’s unclear whether or not the protagonist of the film is simply experiencing a rash of extremely poor luck and cracking under the psychological strain of so many consecutive tragedies, or legitimately being antagonized by a supernatural force.

The Beautiful Woman would be one of Osore Picture’s more successful films, and the modest profit it generated would allow the brothers to get more creative with their next project, Doragon Returns. And, yes - even though the monster is not called Doragon, that really was the name they went with. I don’t get it, either.

Doragon Returns would improve upon the original in multiple ways. While the movie was still filmed in black-and-white, the cameras used to record were of higher quality, resulting in an overall better, more crisp image. The sound quality, too, would see a drastic improvement, with the orchestral music sounding as if it were recorded in a studio rather than an empty, open warehouse. Though, the strange dichotomy between orchestral music and the garage psych rock of Kazuo’s band still exists, with the latter providing several tracks that play at some of the least - and most - opportune moments in the film. For instance, there is a scene in which a column of tanks are annihilated during a drum solo, which, impressive as the drummer’s talent is, doesn’t quite match the level of emotional gravitas that the rest of the film is trying to meet.

The construction of the model cities is markedly better than in the first film, though there are one or two scenes with very cheap, very questionable quality of the models are on full display.

Wotori itself - or, maybe I should say, herself, since it’s revealed that the monster is actually a female - also experienced something of a facelift between films. Though she kept her same general build and design, there was more detail put into the puppet this time around, most notably adding thin, slitted pupils to the creatures white, featureless eyes. This detail may sound minor - and it is - but, of all of Wotori’s design components, the featureless white eyes from her original iteration always gave her a deeply unsettling appearance. The U.S.S. Montana attack scene in the first Doragon, despite the chincy toy ship used as a prop, will always be a highlight of the movie, if only because of the horrible, glassy-eyed stare of the Wotori puppet as it rises out of the black water. I’ve seen fans claim that the added pupils give the monster a more organic and natural appearance rather than that of some other-worldly or ghostly creature, but in my opinion, the featureless white eyes of the original captured the truly inhuman and alien force of nature concept that the Hino brothers wanted to make Wotori out to be.

As for the plot of the movie, the brothers followed the tried-and-true pattern of kaiju movies and introduced a monstrous antagonist for the slightly-less-antagonistic Wotori to do combat with. A professor of biology at the University of Tokyo comes to Aomori to study biological samples left behind by Wotori’s rampage in the immediate aftermath of the attack and runs afoul of the United States military as they seek to obtain the same material. The professor is effectively kidnapped by the American military and put aboard a ship alongside the Shinto priestess that put a stop to Wotori’s attach in the first movie. Said priestess is now being held as a prisoner of the United States government as a means of defense should a similar event occur. It’s this priestess that explains that Wotori is female, ancient, and a naturally peaceful creature that traditionally served as a guardian of the seas around Aomori. It was the meddling of the United States caused her to fly into a rage and attack.

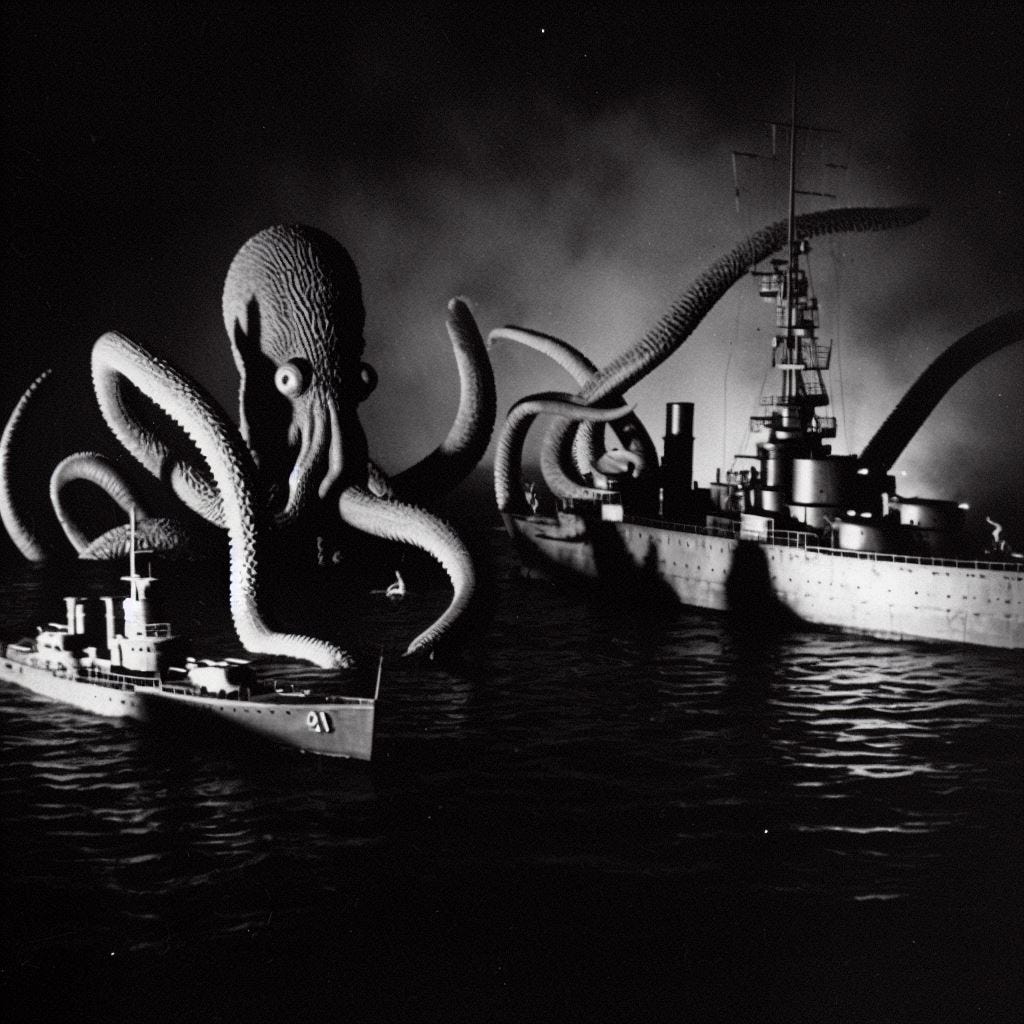

Of course, the United States government has already located another kaiju in the sea off the coast of the Aomori Prefecture - this one a large, kraken-like monster, lying dormant on the sea floor of the Mutsu Bay. In an attempt to preemptively kill the monster, navy submarines begin to torpedo the slumbering beast. Of course, it wakes up. It is not happy. Several United States navy vessels are ensnared by rubber tentacles and dragged to the bottom of a pool.

I also have to mention that, this time, it seemed that Osore Pictures had enough money budgeted to hire caucasians to play the part of American military personnel. Given the stiffness with which they perform, I doubt they were actors so much as the only white people that the Hino brothers could find, and they don't try to hide the fact that they never have more than the same four men playing various military people in different scenes.

The kraken - given the endearing nickname of Tako-san by fans - rises from the briny depths, clambers onto land, and begins to lay waste to the city of Aomori, which, for reasons unbeknownst to me, is almost fully and inexplicably reconstructed after the first attack by Wotori.

The professor and the Shinto priestess escape the confines of their ship with the aid of a sympathetic Japanese liaison, who frees them from the ship’s brig shortly before Tako-san destroys the vessel, along with the disrespectful captain that abducted the two to begin with. In an interesting twist, when the professor suggests that Wotori be brought to do battle with Tako-san, the priestess tells him that the battle between humanity and Tako-san is not Wotori’s to fight.

When Wotori does make an appearance, it’s only after Aomori City has been leveled by Tako-san, and the United States once again rousing her ire by shelling her island and drawing her to Tako-san’s location. The two kaiju do battle over the ruins of Aomori, which ends with Wotori claiming victory as she violently yanks the writhing tentacles off the overgrown mollusk, replete with fountains of black, inky blood spewing from the flailing stumps. Once Tako-san is defeated, however, the United States ship - another fictional battleship, the U.S.S. Ohio - is promptly sunk by Wotori as she turns her attention to the various military forces present. The subtext is, again, difficult to miss.

The professor, bewildered by Wotori’s sudden attack on the military, asks the priestess why the monster would turn on humanity. The priestess then explains in an emotional monologue that Wotori is no friend of humanity’s, and she certainly isn’t an amicable ally to be called upon to protect it during times of need. The United States, just as before, provoked the beast into attacking, and, naturally, she is defending herself and her territory. The final shot of the movie is that of the priestess and the professor watching Wotori lumber further south, down the coast of Honshu and towards the city of Sendai. The former laments that some tricks cannot be performed twice, suggesting that the ritual she used to subdue the monster once will not work a second time.

The ending of Doragon Returns is quite clearly a stab at the direction that the Godzilla films had begun to drift by 1965, in which the eponymous kaiju had taken on more of a benevolent protector role and defended Japan from various monsters - including a giant ape. Clearly, the Hino brothers were not fond of the change in Godzilla’s demeanor, and wanted to keep Wotori as a force of nature that was ultimately ambivalent to humanity.

Overall, though, it seems that Doragon Returns is regarded as lesser than the first by fans. In spite of the technical improvements, fan critique the heavier emphasis on human characters over kaiju action, as well as a lack of development given to the adversarial Tako-san. Where as Godzilla Raids Again introduced Anguiras, who would go on to be an icon of the genre itself, Tako-san is neither as well-designed or memorable. Still, to say that it’s disliked would be a stretch. The general consensus among fans seems to be that, while inferior to the first Doragon, Doragon Returns is still an enjoyable entry into the series, and worth a watch if it can be found.

I very much appreciate that these movie plots are written such that i can tell you know your Godzilla. Have a personal favorite if i may ask?

I'm not sure if this is creepypasta or a typo, but here it is anyway: Fun fact: both the U.S.S. Montana and the U.S.S. Montana were planned battleships belonging to the Montana-class,